Duck Soup

...dog paddling through culture, technology, music and more.

Monday, April 7, 2025

Nutnick

via:

[ed. Ugh. Our so-called Commerce Secretary. I'd say this guy is the absolute worst but there's too much competition. Remember when he told us his mother-in-law wouldn't complain about missing a monthy Social Security check because only "fraudsters" would? What isn't shown here is his next few words..."and it's going to be automated. And the trade craft of America, is going work on them and fix them." Robots presumably. You can view the video here if you can stand it.]

[ed. Ugh. Our so-called Commerce Secretary. I'd say this guy is the absolute worst but there's too much competition. Remember when he told us his mother-in-law wouldn't complain about missing a monthy Social Security check because only "fraudsters" would? What isn't shown here is his next few words..."and it's going to be automated. And the trade craft of America, is going work on them and fix them." Robots presumably. You can view the video here if you can stand it.]

One Agency That Explains What Government Does For You

Tens of thousands of federal workers have been fired recently, and more may be in danger of being let go.

Umair Irfan — a climate change, energy policy, and science correspondent for Vox — has been specifically focused on layoffs looming over the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of late. His reporting presents a great lens for understanding the firings, and he and I discussed what the NOAA can tell us about the effect federal reductions have on everyday Americans. Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, is below.

Umair, what’s NOAA and why is it so important?

NOAA is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It’s tasked with developing weather forecasts for the United States, conducting oceanographic and atmospheric research, and developing long-term climate and weather models. It’s also in charge of fisheries and promoting commerce, particularly in the oceans, which means it does a lot of navigation and mapping work for shipping, and for offshore oil and gas drilling. [ed. and providing scientifc support to the Coast Guard during oil spills].

There have been reports that as much as half of NOAA staff might be dismissed. What would everyday Americans lose if that happened?

NOAA has a staff of about 12,000 people, most of them scientists and engineers. If you lost half of that, you’d lose a lot of people doing the research that informs our weather forecasts and our understanding of weather, as well as a lot of the data that industry players rely on for things like aviation and air travel. We’d also lose a lot of our emergency forecasting capability for extreme weather.

NOAA is one of the reasons that air travel is so safe, and one of the reasons that we’ve seen fewer people dying in natural disasters in the US: It has done the work of putting satellites into space, of having scientific ships on the ocean, and aircraft that fly into hurricanes, and has used its decades of data gathering to develop excellent forecasting capability — and one that, through continual work, is improving all the time.

If we lose all those capabilities, we lose a lot of progress that has been made. Extreme weather will stay dangerous, however, and our ability to drive the risks involved with weather down over time will eventually diminish if we don’t continue to invest in that.

NOAA obviously isn’t the only agency that’s facing cuts here. Do Americans gain anything by shrinking the government the way Trump has been?

Current and former agency staffers and leaders I talked to say the cuts aren’t going to help agencies accomplish their missions, and will actually run counter to any goals of efficiency, because remaining employees will have to try to fulfill the functions of their fired colleagues in suboptimal ways.

That said, there’s always going to be room to optimize a big institution like the government. But we need to do so thoughtfully, stepping back and seeing what our needs are, and what our expectations are from government in general.

Specifically looking at an agency like NOAA, it’s about looking carefully at exactly how its core functions are being met, where they’re falling short, and where they can be augmented. So far, we really haven’t seen that level of exploration and interest in how these agencies function from the current administration.

Big picture, what do you think Americans should learn from the case of NOAA?

I think it’s easy to forget that the federal government is everywhere in our country — 80 percent of federal employees are not in DC.

NOAA is one of those agencies that has a very far-flung footprint, because it has to do a lot of the local research and data gathering on site, and because its mission is to protect the whole country.

And NOAA, like all agencies, is very closely linked to people’s lives in ways they may not expect. You may not have a NOAA app on your phone, but very likely the weather app you do have, and the forecast that you’re getting from your local TV meteorologist, are informed by NOAA’s satellites and data gathering.

While there may be layers in between the products you consume and the government, it does provide the foundation for things we take for granted. If agencies like NOAA go away, we would definitely lose things we might not expect.

by Sean Collins and Umair Irfan, Vox | Read more:

Umair Irfan — a climate change, energy policy, and science correspondent for Vox — has been specifically focused on layoffs looming over the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of late. His reporting presents a great lens for understanding the firings, and he and I discussed what the NOAA can tell us about the effect federal reductions have on everyday Americans. Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, is below.

Umair, what’s NOAA and why is it so important?

NOAA is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It’s tasked with developing weather forecasts for the United States, conducting oceanographic and atmospheric research, and developing long-term climate and weather models. It’s also in charge of fisheries and promoting commerce, particularly in the oceans, which means it does a lot of navigation and mapping work for shipping, and for offshore oil and gas drilling. [ed. and providing scientifc support to the Coast Guard during oil spills].

There have been reports that as much as half of NOAA staff might be dismissed. What would everyday Americans lose if that happened?

NOAA has a staff of about 12,000 people, most of them scientists and engineers. If you lost half of that, you’d lose a lot of people doing the research that informs our weather forecasts and our understanding of weather, as well as a lot of the data that industry players rely on for things like aviation and air travel. We’d also lose a lot of our emergency forecasting capability for extreme weather.

NOAA is one of the reasons that air travel is so safe, and one of the reasons that we’ve seen fewer people dying in natural disasters in the US: It has done the work of putting satellites into space, of having scientific ships on the ocean, and aircraft that fly into hurricanes, and has used its decades of data gathering to develop excellent forecasting capability — and one that, through continual work, is improving all the time.

If we lose all those capabilities, we lose a lot of progress that has been made. Extreme weather will stay dangerous, however, and our ability to drive the risks involved with weather down over time will eventually diminish if we don’t continue to invest in that.

NOAA obviously isn’t the only agency that’s facing cuts here. Do Americans gain anything by shrinking the government the way Trump has been?

Current and former agency staffers and leaders I talked to say the cuts aren’t going to help agencies accomplish their missions, and will actually run counter to any goals of efficiency, because remaining employees will have to try to fulfill the functions of their fired colleagues in suboptimal ways.

That said, there’s always going to be room to optimize a big institution like the government. But we need to do so thoughtfully, stepping back and seeing what our needs are, and what our expectations are from government in general.

Specifically looking at an agency like NOAA, it’s about looking carefully at exactly how its core functions are being met, where they’re falling short, and where they can be augmented. So far, we really haven’t seen that level of exploration and interest in how these agencies function from the current administration.

Big picture, what do you think Americans should learn from the case of NOAA?

I think it’s easy to forget that the federal government is everywhere in our country — 80 percent of federal employees are not in DC.

NOAA is one of those agencies that has a very far-flung footprint, because it has to do a lot of the local research and data gathering on site, and because its mission is to protect the whole country.

And NOAA, like all agencies, is very closely linked to people’s lives in ways they may not expect. You may not have a NOAA app on your phone, but very likely the weather app you do have, and the forecast that you’re getting from your local TV meteorologist, are informed by NOAA’s satellites and data gathering.

While there may be layers in between the products you consume and the government, it does provide the foundation for things we take for granted. If agencies like NOAA go away, we would definitely lose things we might not expect.

by Sean Collins and Umair Irfan, Vox | Read more:

Image: Joseph Prezioso/AFP/Getty Images

[ed. I've worked with NOAA scientists throughout my career. Some of the most impressive people I've met.]

Shingles Vaccine Could Help Stave Off Dementia

According to a study that followed more than 280,000 people in Wales, older adults who received a vaccine against shingles were 20 percent less likely to develop dementia in the seven years that followed vaccination than those who did not receive the vaccine.

“If you’re reducing the risk of dementia by 20 percent, that’s quite important in a public health context, given that we don’t really have much else at the moment that slows down the onset of dementia,” said Dr. Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at Oxford. (...)

This could be a big deal. There are very few, if any, treatments that can prevent or slow down dementia, beyond good lifestyle habits like getting enough sleep and exercise. The possibility that a known, inexpensive vaccine could offer real protection is enormously meaningful. We have good reason to be confident in the findings: While this study is perhaps the most prominent to show the protective effects of the shingles vaccine, other studies of the vaccine have come to similar conclusions.

Beyond the promise of preventive treatment, the new study adds further evidence to a growing body of research raising the possibility that we have been thinking about neurodegenerative diseases like dementia and Alzheimer’s all wrong. It’s possible these horrible conditions are caused by a virus — and if that’s the case, eliminating the virus could be enough to prevent or treat the diseases.

How the study worked

To understand why the new shingles vaccine study is such a big deal, it helps to know a little bit about how medical studies are carried out. (...)

The new study... took advantage of a quirk in Welsh health policy to do something better. Beginning on September 1, 2013, anyone in Wales who was 79 became eligible to receive a free shingles vaccine. (Those who were younger than 79 would become eligible once they turned that age.) But anyone who was 80 or older was not eligible on the grounds that the vaccine is less effective for the very old.

The result was what is known as a “natural experiment.” In effect, Wales had created two groups that were essentially the same — save for the fact that one group received the shingles vaccine and one group did not.

The researchers looked at the health records of the more than 280,000 adults who were 71 to 88 years old at the start of the vaccination program and did not have dementia. They focused on a group that was just on the dividing line: those who turned 80 just before September 1, 2013, and thus were eligible for the vaccine, and those born just after that date, who weren’t. Then, they simply looked at what happened to them.

By 2020, seven years after the vaccination program began, about one in eight older adults, who by that time were 86 and 87, had developed dementia. But the group that had received the shingles vaccine were 20 percent less likely to be diagnosed with the disease. Because the researchers could find no other confounding factors that might explain the difference — like years of education or other vaccines or health conditions like diabetes — they were confident the shingles vaccine was the difference maker.

A new paradigm in dementia research?

As Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford who was not involved in the study, told the New York Times, the research indicates that the shingles vaccine appears to have “some of the strongest potential protective effects against dementia that we know of that are potentially usable in practice.”

But this is a vaccine originally designed to prevent shingles. Why does it also appear to help with dementia?

Scientists theorize it could be related to inflammation. Shingles, or herpes zoster, is caused by the same virus responsible for chickenpox, which lies dormant in nerve cells after an initial infection and can reawaken decades later, causing painful rashes.

That reactivation creates intense inflammation around nerve cells, and chronic inflammation is increasingly recognized as a major factor in cognitive deterioration. By preventing shingles, the vaccine could indirectly protect against the neural inflammation associated with dementia.

What about the amyloid and tau protein plaques that tend to be found in the brains of people suffering from Alzheimer’s, which have long been thought of as the primary cause of the disease? It’s possible that these may actually be the body’s response to an underlying infection. That could help explain why treatments that directly target those plaques have been largely ineffective — because they weren’t targeting the real causes.

Beyond the promise of preventive treatment, the new study adds further evidence to a growing body of research raising the possibility that we have been thinking about neurodegenerative diseases like dementia and Alzheimer’s all wrong. It’s possible these horrible conditions are caused by a virus — and if that’s the case, eliminating the virus could be enough to prevent or treat the diseases.

How the study worked

To understand why the new shingles vaccine study is such a big deal, it helps to know a little bit about how medical studies are carried out. (...)

The new study... took advantage of a quirk in Welsh health policy to do something better. Beginning on September 1, 2013, anyone in Wales who was 79 became eligible to receive a free shingles vaccine. (Those who were younger than 79 would become eligible once they turned that age.) But anyone who was 80 or older was not eligible on the grounds that the vaccine is less effective for the very old.

The result was what is known as a “natural experiment.” In effect, Wales had created two groups that were essentially the same — save for the fact that one group received the shingles vaccine and one group did not.

The researchers looked at the health records of the more than 280,000 adults who were 71 to 88 years old at the start of the vaccination program and did not have dementia. They focused on a group that was just on the dividing line: those who turned 80 just before September 1, 2013, and thus were eligible for the vaccine, and those born just after that date, who weren’t. Then, they simply looked at what happened to them.

By 2020, seven years after the vaccination program began, about one in eight older adults, who by that time were 86 and 87, had developed dementia. But the group that had received the shingles vaccine were 20 percent less likely to be diagnosed with the disease. Because the researchers could find no other confounding factors that might explain the difference — like years of education or other vaccines or health conditions like diabetes — they were confident the shingles vaccine was the difference maker.

A new paradigm in dementia research?

As Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford who was not involved in the study, told the New York Times, the research indicates that the shingles vaccine appears to have “some of the strongest potential protective effects against dementia that we know of that are potentially usable in practice.”

But this is a vaccine originally designed to prevent shingles. Why does it also appear to help with dementia?

Scientists theorize it could be related to inflammation. Shingles, or herpes zoster, is caused by the same virus responsible for chickenpox, which lies dormant in nerve cells after an initial infection and can reawaken decades later, causing painful rashes.

That reactivation creates intense inflammation around nerve cells, and chronic inflammation is increasingly recognized as a major factor in cognitive deterioration. By preventing shingles, the vaccine could indirectly protect against the neural inflammation associated with dementia.

What about the amyloid and tau protein plaques that tend to be found in the brains of people suffering from Alzheimer’s, which have long been thought of as the primary cause of the disease? It’s possible that these may actually be the body’s response to an underlying infection. That could help explain why treatments that directly target those plaques have been largely ineffective — because they weren’t targeting the real causes.

by Bryan Walsh, Vox | Read more:

Image: H. Rick Bamman/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News

[ed. See also: Shingles Vaccine Can Decrease Risk of Dementia, Study Finds (NYT):]

***

The study, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, found that people who received the shingles vaccine were 20 percent less likely to develop dementia in the seven years afterward than those who were not vaccinated.“If you’re reducing the risk of dementia by 20 percent, that’s quite important in a public health context, given that we don’t really have much else at the moment that slows down the onset of dementia,” said Dr. Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at Oxford. (...)

Several previous studies have suggested that shingles vaccinations might reduce dementia risk, but most could not exclude the possibility that people who get vaccinated might have other dementia-protective characteristics, like healthier lifestyles, better diets or more years of education.

The new study ruled out many of those factors. (...)

They also examined medical records for possible differences between the vaccinated and unvaccinated. They evaluated whether unvaccinated people received more diagnoses of dementia simply because they visited doctors more frequently, and whether they took more medications that could increase dementia risk.

“They do a pretty good job at that,” said Dr. Jena, who wrote a commentary about the study for Nature. “They look at almost 200 medications that have been shown to be at least associated with elevated Alzheimer’s risk.”

He said, “They go through a lot of effort to figure out whether or not there might be other things that are timed with that age cutoff, any other medical policy changes, and that doesn’t seem to be it.”

The study involved an older form of shingles vaccine, Zostavax, which contains a modified version of the live virus. It has since been discontinued in the United States and some other countries because its protection against shingles wanes over time. The new vaccine, Shingrix, which contains an inactivated portion of the virus, is more effective and lasting, research shows.

A study last year by Dr. Harrison and colleagues suggested that Shingrix may be more protective against dementia than the older vaccine. Based on another “natural experiment,” the 2017 shift in the United States from Zostavax to Shingrix, it found that over six years, people who had received the new vaccine had fewer dementia diagnoses than those who got the old one. Of the people diagnosed with dementia, those who received the new vaccine had nearly six months more time before developing the condition than people who received the old vaccine.

The new study ruled out many of those factors. (...)

They also examined medical records for possible differences between the vaccinated and unvaccinated. They evaluated whether unvaccinated people received more diagnoses of dementia simply because they visited doctors more frequently, and whether they took more medications that could increase dementia risk.

“They do a pretty good job at that,” said Dr. Jena, who wrote a commentary about the study for Nature. “They look at almost 200 medications that have been shown to be at least associated with elevated Alzheimer’s risk.”

He said, “They go through a lot of effort to figure out whether or not there might be other things that are timed with that age cutoff, any other medical policy changes, and that doesn’t seem to be it.”

The study involved an older form of shingles vaccine, Zostavax, which contains a modified version of the live virus. It has since been discontinued in the United States and some other countries because its protection against shingles wanes over time. The new vaccine, Shingrix, which contains an inactivated portion of the virus, is more effective and lasting, research shows.

A study last year by Dr. Harrison and colleagues suggested that Shingrix may be more protective against dementia than the older vaccine. Based on another “natural experiment,” the 2017 shift in the United States from Zostavax to Shingrix, it found that over six years, people who had received the new vaccine had fewer dementia diagnoses than those who got the old one. Of the people diagnosed with dementia, those who received the new vaccine had nearly six months more time before developing the condition than people who received the old vaccine.

Sunday, April 6, 2025

World’s Largest Wildlife Crossing Takes Shape in Los Angeles

‘Even a freeway is redeemable’: world’s largest wildlife crossing takes shape in Los Angeles (The Guardian)

Image: Caltrans

The plot is a native wildlife habitat that connects two parts of the Santa Monica mountain range, with the hopes of saving creatures – from the famous local mountain lions, down to frogs and insects – from being crushed by cars on one of the nation’s busiest roadways.[ed. Wow, this is crazy. What are they connecting to, exactly? And what are the numbers/science that support this? I and a few other biologists in my department (Alaska Dept. Fish and Game) pioneered wildlife crossings back in the 70s when North Slope oil fields were just starting to get developed. Most of you probably don't remember all those magazine and tv ads from industry back then boasting about their deep commitment to the environment and sensitivity to wildlife? Haha... well, not quite. It was a constant fight to get even a few caribou pipeline crossings installed so that thousands of animals could have continued access to feeding and calving areas along the coast. Too expensive and unnecessary, wouldn't work. Of course, once those crossings were installed and found to be effective, companies were only too happy to take credit. And these were just 30-40 foot gravel pads. In later years near Anchorage, when moose/automobile collisions started becoming epidemic (as the city started expanding highway lanes in outlying areas), more of the same fights, this time with the military whose lands the highway transited, and state DOT who again objected to 'wasting' money. Cost and effectiveness issues, as always. So, a compromise - fencing, one-way gates, and underpasses instead. Which worked amazingly well, and continue to do so today. Which isn't to say that some overhead crossings aren't warranted in some places (we have one here in Washington over I-90 that works well for large and small mammals). But something like this California project would have been a non-starter back in the old days unless there's some critical importance for that particular spot, which isn't mentioned in the article. Definitely more than the occasional mountain lion, frogs and insects. But it's California, who knows.]

Benefits of ADHD Medication Outweigh Health Risks, Study Finds

The benefits of taking drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder outweigh the impact of increases in blood pressure and heart rate, according to a new study.

An international team of researchers led by scientists from the University of Southampton found the majority of children taking ADHD medication experienced small increases in blood pressure and pulse rates, but that the drugs had “overall small effects”. They said the study’s findings highlighted the need for “careful monitoring”.

Prof Samuele Cortese, the senior lead author of the study, from the University of Southampton, said the risks and benefits of taking any medication had to be assessed together, but for ADHD drugs the risk-benefit ratio was “reassuring”.

“We found an overall small increase in blood pressure and pulse for the majority of children taking ADHD medications,” he said. “Other studies show clear benefits in terms of reductions in mortality risk and improvement in academic functions, as well as a small increased risk of hypertension, but not other cardiovascular diseases. Overall, the risk-benefit ratio is reassuring for people taking ADHD medications.”

About 3 to 4% of adults and 5% of children in the UK are believed to have ADHD, a neurodevelopmental disorder with symptoms including impulsiveness, disorganisation and difficulty focusing, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice).

Doctors can prescribe stimulants, such as methylphenidate, of which the best-known brand is Ritalin. Other stimulant medications used to treat ADHD include lisdexamfetamine and dexamfetamine. Non-stimulant drugs include atomoxetine, an sNRI (selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor), and guanfacine.(...)

Last year, a thinktank warned that the NHS was experiencing an “avalanche of need” over autism and ADHD, and said the system in place to cope with surging demand for assessments and treatments was “obsolete”. The number of prescriptions issued in England for ADHD medication has risen by 18% year on year since the pandemic, with the biggest rise in London.

Dr Tony Lord, a former chief executive of the ADHD Foundation, said the long-term benefits of ADHD medication were well established, and included a reduced risk of anxiety and depression, eating disorders, harm from smoking, improved educational outcomes and economic independence.

“Sadly ignorance about ADHD medications persists – a throwback to the 80s and 90s when ADHD medications were mistakenly viewed as a morality pill that made naughty, fidgety disruptive children behave – which of course it is not,” he said.

“It is simply a cognitive enhancer that improves information processing, inhibits distractions, improves focus, planning and prioritising, self monitoring and reduces impulsivity of thought and action.”

An international team of researchers led by scientists from the University of Southampton found the majority of children taking ADHD medication experienced small increases in blood pressure and pulse rates, but that the drugs had “overall small effects”. They said the study’s findings highlighted the need for “careful monitoring”.

Prof Samuele Cortese, the senior lead author of the study, from the University of Southampton, said the risks and benefits of taking any medication had to be assessed together, but for ADHD drugs the risk-benefit ratio was “reassuring”.

“We found an overall small increase in blood pressure and pulse for the majority of children taking ADHD medications,” he said. “Other studies show clear benefits in terms of reductions in mortality risk and improvement in academic functions, as well as a small increased risk of hypertension, but not other cardiovascular diseases. Overall, the risk-benefit ratio is reassuring for people taking ADHD medications.”

About 3 to 4% of adults and 5% of children in the UK are believed to have ADHD, a neurodevelopmental disorder with symptoms including impulsiveness, disorganisation and difficulty focusing, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice).

Doctors can prescribe stimulants, such as methylphenidate, of which the best-known brand is Ritalin. Other stimulant medications used to treat ADHD include lisdexamfetamine and dexamfetamine. Non-stimulant drugs include atomoxetine, an sNRI (selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor), and guanfacine.(...)

Last year, a thinktank warned that the NHS was experiencing an “avalanche of need” over autism and ADHD, and said the system in place to cope with surging demand for assessments and treatments was “obsolete”. The number of prescriptions issued in England for ADHD medication has risen by 18% year on year since the pandemic, with the biggest rise in London.

Dr Tony Lord, a former chief executive of the ADHD Foundation, said the long-term benefits of ADHD medication were well established, and included a reduced risk of anxiety and depression, eating disorders, harm from smoking, improved educational outcomes and economic independence.

“Sadly ignorance about ADHD medications persists – a throwback to the 80s and 90s when ADHD medications were mistakenly viewed as a morality pill that made naughty, fidgety disruptive children behave – which of course it is not,” he said.

“It is simply a cognitive enhancer that improves information processing, inhibits distractions, improves focus, planning and prioritising, self monitoring and reduces impulsivity of thought and action.”

by Alexandra Topping, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Murdo Macleod/The Guardian

[ed. I'd love to get an Adderall prescription as a cognitive enhancer (more energy - and a history of chronic anemia and depression). But not willing to fake ADHD, and doctors won't prescribe it (unless you're rich, influencial or have a job in finance).]

[ed. I'd love to get an Adderall prescription as a cognitive enhancer (more energy - and a history of chronic anemia and depression). But not willing to fake ADHD, and doctors won't prescribe it (unless you're rich, influencial or have a job in finance).]

Bad Taste or No Taste?

Images:Diggzy/Backgrid, Edward Berthelot, Jacopo Raule/Getty Images

The real star of The White Lotus? Natural teeth (Harper's Bazaar). [See also: How this 'White Lotus' star's teeth stole the show — and sparked a reckoning (MSNBC).]

[ed. Almost feel sorry for them. Fashion for late-stage capitalism. It must take a lot of effort just to keep those fashion antenna up (no matter how ridiculous, but what else do they have to do?). Fortunately, there's a more hopeful trend:]

The real star of The White Lotus? Natural teeth (Harper's Bazaar). [See also: How this 'White Lotus' star's teeth stole the show — and sparked a reckoning (MSNBC).]

Saturday, April 5, 2025

Technocracy 2.0

The Failed Ideas That Drive Elon Musk

President Trump has reportedly told cabinet members that Elon Musk may soon leave the administration. If and when he goes, what will he leave behind?

Mr. Musk has long presented himself to the world as a futurist. Yet, notwithstanding the gadgets — the rockets and the robots and the Department of Government Efficiency Musketeers, carrying backpacks crammed with laptops, dreaming of replacing federal employees with large language models — few figures in public life are more shackled to the past.

On the day of Donald Trump’s inauguration, Mr. Musk told a roaring, jubilant crowd that the election marked “a fork in the road of human civilization.” He promised to “take DOGE to Mars” and pledged to give Americans reasons to look “forward to the future.”

In 1932, when civilization stood at another fork in the road, the United States chose liberal democracy, and Franklin Roosevelt, who promised “a new deal for the American people.” In his first 100 days, Mr. Roosevelt. signed 99 executive orders, and Congress passed more than 75 laws, beginning the work of rebuilding the country by establishing a series of government agencies to regulate the economy, provide jobs, aid the poor and construct public works.

Mr. Musk is attempting to go back to that fork and choose a different path. Much of what he has sought to dismantle, from antipoverty programs to national parks, have their origins in the New Deal. Mr. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration provided 8.5 million Americans with jobs; Mr. Musk has measured his achievement in the number of jobs he has eliminated.

Four years ago, I made a series for the BBC in which I located the origins of Mr. Musk’s strange sense of destiny in science fiction, some of it a century old. This year, revising the series, I was again struck at how little of what Mr. Musk proposes is new and by how many of his ideas about politics, governance and economics resemble those championed by his grandfather Joshua Haldeman, a cowboy, chiropractor, conspiracy theorist and amateur aviator known as the Flying Haldeman. Mr. Musk’s grandfather was also a flamboyant leader of the political movement known as technocracy.

Leading technocrats proposed replacing democratically elected officials and civil servants — indeed, all of government — with an army of scientists and engineers under what they called a technate. Some also wanted to annex Canada and Mexico. At technocracy’s height, one branch of the movement had more than a quarter of a million members.

Under the technate, humans would no longer have names; they would have numbers. One technocrat went by 1x1809x56. (Mr. Musk has a son named X Æ A-12.) Mr. Haldeman, who had lost his Saskatchewan farm during the Depression, became the movement’s leader in Canada. He was technocrat No. 10450-1.

Technocracy first gained worldwide attention in 1932 but soon splintered into rival factions. Technocracy Incorporated was founded and led by a former New Yorker named Howard Scott. Across the continent, rival groups of technocrats issued a flurry of tracts, periodicals and pamphlets explaining, for instance, how “life in a technocracy” would be utterly different from life in a democracy: “Popular voting can be largely dispensed with.”

Technocrats argued that liberal democracy had failed. One Technocracy Incorporated pamphlet explained how the movement “does not subscribe to the basic tenet of the democratic ideal, namely that all men are created free and equal.” In the modern world, only scientists and engineers have the intelligence and education to understand the industrial operations that lie at the heart of the economy. Mr. Scott’s army of technocrats would eliminate most government services: “Even our postal system, our highways, our Coast Guard could be made much more efficient.” Overlapping agencies could be shuttered, and “90 percent of the courts could be abolished.”

Decades ago, in the desperate, darkest moment of the Depression, technocracy seemed, briefly, poised to prevail against democracy. “For a moment in time, it was possible for thoughtful people to believe that America would consciously choose to become a technocracy,” writes William E. Akin, the author of the definitive historical study of the movement, “Technocracy and the American Dream.” In the four months from November 1932 to March 1933, The New York Times published more than 100 stories about the movement. And then the bubble appeared to burst. By summer, Technocrats Magazine and The Technocracy Review had gone out of print.

There are a few reasons for technocracy’s implosion. Its tenets could not bear scrutiny. Then, too, because technocrats generally did not believe in parties, elections or politics of any kind — “Technocracy has no theory for the assumption of power,” as Mr. Scott put it — they had little means by which to achieve their ends.

But the chief reason for technocracy’s failure was democracy’s success. Mr. Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4 and immediately began putting the New Deal in place while calming the nation with a series of fireside chats. By May, E.B. White in The New Yorker could write technocracy’s epitaph: “Technocracy had its day this year, and it was characteristic of Americans that they gave it a whirl and then dropped it as they had dropped miniature golf.”

Nevertheless, technocracy endured. Its spectacles grew alarming: Technocrats wore identical gray suits and drove identical gray cars in parades that evoked for concerned observers nothing so much as Italian Fascists. Mr. Musk’s grandfather was a technocracy stalwart. In 1940, when Canada banned Technocracy Incorporated — out of fear that its members were plotting to undermine the government or the war effort — Mr. Haldeman took out an ad in a newspaper, proclaiming technocracy a “national patriotic movement.” (...)

That Mr. Musk has come to hold so many of the same beliefs about social engineering and economic planning as his grandfather is a testament to his profound lack of political imagination, to the tenacity of technocracy and to the hubris of Silicon Valley.

Mr. Musk left South Africa for Canada in 1989, where he stayed with family in Saskatchewan. His grandfather’s memory loomed large; not long afterward, his uncle Scott Haldeman, who had left Pretoria to pursue graduate studies in British Columbia, wrote an article in which he described Joshua Haldeman as holding “national and international stature as a political economist.”

In 1995, after studying at the University of Pennsylvania, Mr. Musk left a Ph.D. program at Stanford to become a tech entrepreneur. He started a company called X.com in 1999. “What we’re going to do is transform the traditional banking industry,” he said. (Technocrats also planned to abolish banks. “We don’t need banks, bandits or bastards,” Joshua Haldeman once wrote.) Mr. Musk made a fortune when eBay acquired PayPal, which had merged with X.com, but in 2017 he bought back the URL, and it was ready to hand when he purchased Twitter and renamed it X, hoping to kill what he called the “woke mind virus” — echoes of his grandfather’s “mass mind conditioning.” Much that Mr. Musk has attempted to do at DOGE can be found in the technocracy manuals of the early 1930s.

Mr. Musk’s possible departure from Washington will not diminish the influence of Muskism in the United States. His superannuated futurism is Silicon Valley’s reigning ideology. In 2023 the venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, who helped staff DOGE, wrote “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto," predicting the emergence of “technological supermen.” It consists of a list of statements:

Muskism isn’t the beginning of the future. It’s the end of a story that started more than a century ago, in the conflict between capital and labor and between autocracy and democracy. The Gilded Age of robber barons and wage-labor strikes gave rise to the Bolshevik Revolution, Communism, the first Red Scare, World War I and Fascism. That battle of ideas produced the technocracy movement, and far more lastingly, it also produced the New Deal and modern American liberalism. Technocracy lost because technocracy is incompatible with freedom.

That is still true, but unlike his forefathers, Mr. Musk does have a theory for the assumption of power. That theory is to seize power with the dead robotic hand of the past.

Mr. Musk has long presented himself to the world as a futurist. Yet, notwithstanding the gadgets — the rockets and the robots and the Department of Government Efficiency Musketeers, carrying backpacks crammed with laptops, dreaming of replacing federal employees with large language models — few figures in public life are more shackled to the past.

On the day of Donald Trump’s inauguration, Mr. Musk told a roaring, jubilant crowd that the election marked “a fork in the road of human civilization.” He promised to “take DOGE to Mars” and pledged to give Americans reasons to look “forward to the future.”

In 1932, when civilization stood at another fork in the road, the United States chose liberal democracy, and Franklin Roosevelt, who promised “a new deal for the American people.” In his first 100 days, Mr. Roosevelt. signed 99 executive orders, and Congress passed more than 75 laws, beginning the work of rebuilding the country by establishing a series of government agencies to regulate the economy, provide jobs, aid the poor and construct public works.

Mr. Musk is attempting to go back to that fork and choose a different path. Much of what he has sought to dismantle, from antipoverty programs to national parks, have their origins in the New Deal. Mr. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration provided 8.5 million Americans with jobs; Mr. Musk has measured his achievement in the number of jobs he has eliminated.

Four years ago, I made a series for the BBC in which I located the origins of Mr. Musk’s strange sense of destiny in science fiction, some of it a century old. This year, revising the series, I was again struck at how little of what Mr. Musk proposes is new and by how many of his ideas about politics, governance and economics resemble those championed by his grandfather Joshua Haldeman, a cowboy, chiropractor, conspiracy theorist and amateur aviator known as the Flying Haldeman. Mr. Musk’s grandfather was also a flamboyant leader of the political movement known as technocracy.

Leading technocrats proposed replacing democratically elected officials and civil servants — indeed, all of government — with an army of scientists and engineers under what they called a technate. Some also wanted to annex Canada and Mexico. At technocracy’s height, one branch of the movement had more than a quarter of a million members.

Under the technate, humans would no longer have names; they would have numbers. One technocrat went by 1x1809x56. (Mr. Musk has a son named X Æ A-12.) Mr. Haldeman, who had lost his Saskatchewan farm during the Depression, became the movement’s leader in Canada. He was technocrat No. 10450-1.

Technocracy first gained worldwide attention in 1932 but soon splintered into rival factions. Technocracy Incorporated was founded and led by a former New Yorker named Howard Scott. Across the continent, rival groups of technocrats issued a flurry of tracts, periodicals and pamphlets explaining, for instance, how “life in a technocracy” would be utterly different from life in a democracy: “Popular voting can be largely dispensed with.”

Technocrats argued that liberal democracy had failed. One Technocracy Incorporated pamphlet explained how the movement “does not subscribe to the basic tenet of the democratic ideal, namely that all men are created free and equal.” In the modern world, only scientists and engineers have the intelligence and education to understand the industrial operations that lie at the heart of the economy. Mr. Scott’s army of technocrats would eliminate most government services: “Even our postal system, our highways, our Coast Guard could be made much more efficient.” Overlapping agencies could be shuttered, and “90 percent of the courts could be abolished.”

Decades ago, in the desperate, darkest moment of the Depression, technocracy seemed, briefly, poised to prevail against democracy. “For a moment in time, it was possible for thoughtful people to believe that America would consciously choose to become a technocracy,” writes William E. Akin, the author of the definitive historical study of the movement, “Technocracy and the American Dream.” In the four months from November 1932 to March 1933, The New York Times published more than 100 stories about the movement. And then the bubble appeared to burst. By summer, Technocrats Magazine and The Technocracy Review had gone out of print.

There are a few reasons for technocracy’s implosion. Its tenets could not bear scrutiny. Then, too, because technocrats generally did not believe in parties, elections or politics of any kind — “Technocracy has no theory for the assumption of power,” as Mr. Scott put it — they had little means by which to achieve their ends.

But the chief reason for technocracy’s failure was democracy’s success. Mr. Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4 and immediately began putting the New Deal in place while calming the nation with a series of fireside chats. By May, E.B. White in The New Yorker could write technocracy’s epitaph: “Technocracy had its day this year, and it was characteristic of Americans that they gave it a whirl and then dropped it as they had dropped miniature golf.”

Nevertheless, technocracy endured. Its spectacles grew alarming: Technocrats wore identical gray suits and drove identical gray cars in parades that evoked for concerned observers nothing so much as Italian Fascists. Mr. Musk’s grandfather was a technocracy stalwart. In 1940, when Canada banned Technocracy Incorporated — out of fear that its members were plotting to undermine the government or the war effort — Mr. Haldeman took out an ad in a newspaper, proclaiming technocracy a “national patriotic movement.” (...)

That Mr. Musk has come to hold so many of the same beliefs about social engineering and economic planning as his grandfather is a testament to his profound lack of political imagination, to the tenacity of technocracy and to the hubris of Silicon Valley.

Mr. Musk left South Africa for Canada in 1989, where he stayed with family in Saskatchewan. His grandfather’s memory loomed large; not long afterward, his uncle Scott Haldeman, who had left Pretoria to pursue graduate studies in British Columbia, wrote an article in which he described Joshua Haldeman as holding “national and international stature as a political economist.”

In 1995, after studying at the University of Pennsylvania, Mr. Musk left a Ph.D. program at Stanford to become a tech entrepreneur. He started a company called X.com in 1999. “What we’re going to do is transform the traditional banking industry,” he said. (Technocrats also planned to abolish banks. “We don’t need banks, bandits or bastards,” Joshua Haldeman once wrote.) Mr. Musk made a fortune when eBay acquired PayPal, which had merged with X.com, but in 2017 he bought back the URL, and it was ready to hand when he purchased Twitter and renamed it X, hoping to kill what he called the “woke mind virus” — echoes of his grandfather’s “mass mind conditioning.” Much that Mr. Musk has attempted to do at DOGE can be found in the technocracy manuals of the early 1930s.

Mr. Musk’s possible departure from Washington will not diminish the influence of Muskism in the United States. His superannuated futurism is Silicon Valley’s reigning ideology. In 2023 the venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, who helped staff DOGE, wrote “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto," predicting the emergence of “technological supermen.” It consists of a list of statements:

We can advance to a far superior way of living and of being.Mr. Andreessen cited, among his inspirations, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who in 1909 wrote “The Futurist Manifesto,” which glorified violence and masculine virility and opposed liberalism and democracy. It, too, is a list of statements:

We have the tools, the systems, the ideas.

We have the will. …

We believe this is why our descendants will live in the stars. …

We believe in greatness. …

We believe in ambition, aggression, persistence, relentlessness — strength.

- We want to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and rashness.

- We want to exalt movements of aggression, feverish sleeplessness, the double march, the perilous leap, the slap and the blow with the fist. …

- We want to sing the man at the wheel. …

- We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism. …

- Standing on the world’s summit, we launch once again our insolent challenge to the stars!

Muskism isn’t the beginning of the future. It’s the end of a story that started more than a century ago, in the conflict between capital and labor and between autocracy and democracy. The Gilded Age of robber barons and wage-labor strikes gave rise to the Bolshevik Revolution, Communism, the first Red Scare, World War I and Fascism. That battle of ideas produced the technocracy movement, and far more lastingly, it also produced the New Deal and modern American liberalism. Technocracy lost because technocracy is incompatible with freedom.

That is still true, but unlike his forefathers, Mr. Musk does have a theory for the assumption of power. That theory is to seize power with the dead robotic hand of the past.

by Jill Lepore, NY Times | Read more:

Image: via

Labels:

Critical Thought,

Government,

history,

Politics,

Relationships,

Technology

This Habit Is Quietly Ruining Your Relationships

The Silent Treatment.

For the uninitiated, the silent treatment is when a person intentionally refuses to communicate with you — or in some cases, even acknowledge you. It’s a common maneuver that’s used in all sorts of relationships, said Kipling Williams, emeritus professor of psychological sciences at Purdue University who has studied the effects of the silent treatment for over 30 years.

The tactic I was using on Tom is one that researchers from the University of Sydney call “noisy silence.” That is when a person tries, in an obvious way, to show the target that he or she is being ignored — such as theatrically leaving the room when the other person enters.

I’m ashamed to say that this was me. When I wordlessly left for work, I glared at Tom and then dramatically slammed the door.

Using the silent treatment is tempting because it can feel good, temporarily, to make the other person squirm, said Erin Engle, a psychologist with NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. But, she added, it can have long-term consequences in your relationship.

I asked experts what to do if you’re getting the silent treatment — or if you’re feeling the urge to give it to someone else.

If you’re tempted to freeze someone out …

Some people think the silent treatment is a milder way of dealing with conflict, said Dr. Gail Saltz, clinical associate professor of psychiatry at the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.

But it isn’t, she explained. “The silent treatment is a punishment,” she said, “whether you are acknowledging that to yourself or not.”

For the person who is being frozen out, it creates “anxiety and fear, and feelings of abandonment,” Dr. Saltz said, and it often causes a “cascade of self-doubt, self-blame and self-criticism.”

And it hurts, Dr. Williams added. His research suggested that being excluded and ignored activates the same pain regions in the brain as physical pain. “So it’s not just metaphorically painful, it is detected as pain by the brain,” he said.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed, ask for a timeout instead, Dr. Williams advised. You can say: “I can’t talk to you right now, I’m so upset. I’m going to go for a walk and I’ll come back in an hour.”

Give a clear time when you will be back and willing to talk, so you don’t leave things open-ended, said James Wirth, an associate professor of psychology at Ohio State University at Newark who studies ostracism. Ambiguity, he said, is part of what makes the silent treatment “really lethal.”

If you’re on the receiving end …

There isn’t much literature on the most effective way to break the silence, Dr. Wirth said. The only true suggestion based on the research, he said, is that it should be stopped.

If you’re up for it, he said, write a note or appeal to the person directly rather than prolonging the silence.

To reestablish connection, try to summon your empathy, Dr. Saltz said. Though she acknowledged that could be hard. “You think, ‘Why can’t they just talk to me?’ Like, ‘This is terrible, no sweat for them,’” she said.

But that’s not necessarily true, she added. The person may have worked themselves into a state of distress, she said. “It actually isn’t easy for them,” she said. “It is hard for them.”

Dr. Saltz suggested approaching the person with openness and curiosity by using the following script: “It makes me feel that we can’t move forward when you’re giving me the silent treatment. I want to understand what’s happening with you. I don’t want you to feel upset. I want to make things better between us. And I need more information about what is happening with you in order to do that.”

And while many of us are guilty of using the silent treatment once in a while, Dr. Saltz added, if, say, a partner is chronically and frequently handling all conflict this way, then “it’s fair to qualify that as emotional abuse.”

I’m ashamed to say that this was me. When I wordlessly left for work, I glared at Tom and then dramatically slammed the door.

Using the silent treatment is tempting because it can feel good, temporarily, to make the other person squirm, said Erin Engle, a psychologist with NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. But, she added, it can have long-term consequences in your relationship.

I asked experts what to do if you’re getting the silent treatment — or if you’re feeling the urge to give it to someone else.

If you’re tempted to freeze someone out …

Some people think the silent treatment is a milder way of dealing with conflict, said Dr. Gail Saltz, clinical associate professor of psychiatry at the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.

But it isn’t, she explained. “The silent treatment is a punishment,” she said, “whether you are acknowledging that to yourself or not.”

For the person who is being frozen out, it creates “anxiety and fear, and feelings of abandonment,” Dr. Saltz said, and it often causes a “cascade of self-doubt, self-blame and self-criticism.”

And it hurts, Dr. Williams added. His research suggested that being excluded and ignored activates the same pain regions in the brain as physical pain. “So it’s not just metaphorically painful, it is detected as pain by the brain,” he said.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed, ask for a timeout instead, Dr. Williams advised. You can say: “I can’t talk to you right now, I’m so upset. I’m going to go for a walk and I’ll come back in an hour.”

Give a clear time when you will be back and willing to talk, so you don’t leave things open-ended, said James Wirth, an associate professor of psychology at Ohio State University at Newark who studies ostracism. Ambiguity, he said, is part of what makes the silent treatment “really lethal.”

And remember: While using the silent treatment may give you a sense of power and control, Dr. Williams said, it’s also draining. It takes work to enforce “this behavior that’s unusual and contrary to norms,” he explained, “so it takes a lot of cognitive effort and a lot of emotional effort.”

If you’re on the receiving end …

There isn’t much literature on the most effective way to break the silence, Dr. Wirth said. The only true suggestion based on the research, he said, is that it should be stopped.

If you’re up for it, he said, write a note or appeal to the person directly rather than prolonging the silence.

To reestablish connection, try to summon your empathy, Dr. Saltz said. Though she acknowledged that could be hard. “You think, ‘Why can’t they just talk to me?’ Like, ‘This is terrible, no sweat for them,’” she said.

But that’s not necessarily true, she added. The person may have worked themselves into a state of distress, she said. “It actually isn’t easy for them,” she said. “It is hard for them.”

Dr. Saltz suggested approaching the person with openness and curiosity by using the following script: “It makes me feel that we can’t move forward when you’re giving me the silent treatment. I want to understand what’s happening with you. I don’t want you to feel upset. I want to make things better between us. And I need more information about what is happening with you in order to do that.”

And while many of us are guilty of using the silent treatment once in a while, Dr. Saltz added, if, say, a partner is chronically and frequently handling all conflict this way, then “it’s fair to qualify that as emotional abuse.”

by Jancee Dunn, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Matt Chase; Photographs by Shutterstock

[ed. Guilty. I have the suspicion that stubborness has something to do with this, too.]

Image: Matt Chase; Photographs by Shutterstock

[ed. Guilty. I have the suspicion that stubborness has something to do with this, too.]

Economic Termites

How the American Medical Association Screws Doctors

One thing that we’re learning in the Trump era is how extensively government power flows throughout our society, as corporations, universities, and law firms scurry to obey the rules that the new administration is putting forward. A few months ago, I found one of these levers in the form of a fee that doctors must pay when they submit medical bills to Medicare or Medicaid. It’s a classic economic termite, a charge that is relatively small such that consumers don’t notice, but one that fosters a significant amount of money for the monopolist. But in this case, there’s a political twist.

But first, let’s go to the problem itself. In January, a reader sent me a note about a fee paid by her father, a licensed marriage and family therapist. Here’s what she said.

Last year, SimplePractice sent out a note to its customers announcing this fee structure, to widespread anger. One therapist noted on Reddit, “I may get hate for this but this is the kind of shit that really makes me want to surrender my license and become a life coach, allowing me to continue helping people but opting out of the racket. I’m so tired of feeling exploited.” Another said, “Like wtf, being in private practice is already hard and expensive enough, these little ass fees add up. I might drop emr and go back to paper.”

CPT codes are a way to explain what a clinician did during an interaction with a patient. For instance, the most common CPT code for psychologists is 90837, which is the number that means the clinician provided an hour of psychotherapy. To get payment, they will submit this code to health insurers, whether private, Medicare, or Medicaid, and everyone involved will know what it means. First developed in 1966 for use with Medicare, the demand for extensive medical documentation is now a serious contributor to physician burnout, as "[f]or every 8 hours of scheduled patient time, ambulatory physicians spend more than 5 hours on the electronic health records." (...)

In other words, the AMA isn’t offering a software product. It just runs this process, keeping a list of codes that map to different medical procedures. You would think it would be free, a standard for everyone to use. But it’s not, and the AMA is able to charge a royalty for the license to use those codes. Every medical software company seems to have CPT codes and royalties built into their workflow.

Other similar systems are public. For instance, there’s the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, which are used by most other countries for free. ICD and CPT codes are complements, not substitutes. ICD is a list of diagnoses- “this patient has depression” “this patient has a pulmonary embolus” while CPT is a list of procedures “I talked to this patient for 60 min” “I did this surgery on this patient.” Most billing systems require both codes, basically the insurer is saying “what did you do” (CPT) and “why” (ICD)? But only one is copyrighted. To put it differently, this situation is a bit like if Fedex owned and designed the zip code system, and got to charge anyone who used a zip code.

The total amount of money to the AMA is relatively small, at least compared to overall cost in our health care system. It’s roughly $300 million a year to the AMA in royalty payments. That’s not nothing; but the impact is far more significant on the politics of health care. To understand why, it helps to start with the importance of this particular trade association.

The AMA is the “doctor’s lobby,” and it has been a powerful force in American politics since it was founded in 1847. The rich American doctor was a 20th century community leader, or a petty tyrant, whichever you might believe. Americans respected their physicians, and doctors were conservative and locally rooted, able to speak with authority on matters of public health. They generally feared the state, but also feared corporate control.

The AMA, as such, jealously guarded this position, routinely opposing government attempts to provide universal health care through a centralized administrative public apparatus, haranguing Democrats as seeking to foster “socialized medicine.” And it worked. The AMA beat Franklin Delano Roosevelt, it beat Harry Truman, and it beat Bill Clinton. The threat of corporatization was perceived by medical professionals as coming from the left.

But in the last 20 years, this dynamic has changed, because most doctors now work for large corporations. The old days of hanging up a shingle in a solo or even small group practice is gone because it’s no longer possible for an individual to bargain with the giants that manage the reimbursements, hospital systems, and payment arrangements necessary to be a doctor. Curiously, the AMA, which one would think has some interest in opposing the mass corporatization of its membership, doesn’t seem to care. For instance, the AMA only took a stance on private equity two years ago, long after its membership had transitioned from majority independent practitioners to majority corporate employees. And a key reason might be because it doesn’t make its money by serving doctors anymore. It makes it from the CPT code monopoly it uses to extract from doctors.

Let’s look at some numbers.

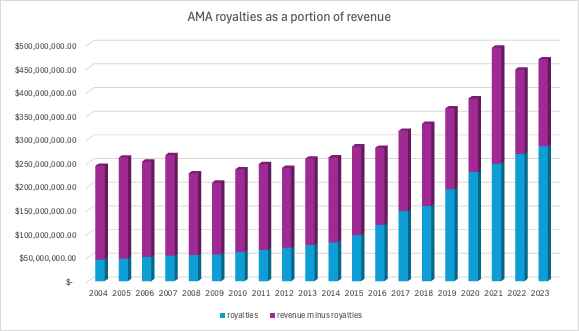

If you look at AMA financial disclosures from 2004 to 2023, you’ll notice three big trends. First of all, dues membership is down. In 2004, it was at $48 million. By 2023, it fell to $33 million. Second of all, revenue is way up, from $243 million to $468 million. And third, there’s an item - “royalties” - that explains it. Royalties, which come largely from CPT code revenue, were about a fifth of the AMA revenue in 2004, at $45 million. In 2023 they were at $308 million, 62% of all revenue, including all the profit, most of the overhead, and the lucrative executive salaries, which have increased by 10x since 2004.

The original CPT codes came out in 1966 to coincide with Medicare, but were published as a book updated annually. It was when electronic medical records took off that the revenue stream picked up. (...)

This situation isn’t just a case of unfair rent extraction, though it is certainly that. It’s also a case of political capture of the AMA. At any point, the Secretary of HHS could choose to revisit its standardization on top of CPT codes, and either foster an alternative, allow competition, or demand that the AMA cut prices. There are alternatives. There are ICD codes. There’s also something called SNOMED, which stands for the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms, which is paid for by at a national level. It’s much cheaper than the CPT codes; Japan, for instance, pays less than $1 million. Switching over to a new system, or even allowing a new system would take a lot of effort. A much simpler change would be Congress passing a law invalidating copyrights for public medial standards, such as CPT codes. It’s ridiculous that a public standard on which everyone must operate is subject to extractive royalty payments. The government has a lot of power here, and could actually start to exert it.

But first, let’s go to the problem itself. In January, a reader sent me a note about a fee paid by her father, a licensed marriage and family therapist. Here’s what she said.

In his practice my dad uses a billing software called SimplePractice and in December they started charging a yearly $20 fee to each clinician. They say this fee is to cover the $18 royalty AMA charges SimplePractice for each clinician who uses the software since the software can use CPT codes, as well as a $2 processing fee.Sure, enough, I went to SimplePractice’s website, and there it is explaining the annual $20 charge for something called a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code. SimplePractice says customers must pay the royalty to the American Medical Association, which “owns the rights to CPT codes and mandates the collection of royalty fees for all clinicians who have access to the codes, regardless of usage.”

Last year, SimplePractice sent out a note to its customers announcing this fee structure, to widespread anger. One therapist noted on Reddit, “I may get hate for this but this is the kind of shit that really makes me want to surrender my license and become a life coach, allowing me to continue helping people but opting out of the racket. I’m so tired of feeling exploited.” Another said, “Like wtf, being in private practice is already hard and expensive enough, these little ass fees add up. I might drop emr and go back to paper.”

CPT codes are a way to explain what a clinician did during an interaction with a patient. For instance, the most common CPT code for psychologists is 90837, which is the number that means the clinician provided an hour of psychotherapy. To get payment, they will submit this code to health insurers, whether private, Medicare, or Medicaid, and everyone involved will know what it means. First developed in 1966 for use with Medicare, the demand for extensive medical documentation is now a serious contributor to physician burnout, as "[f]or every 8 hours of scheduled patient time, ambulatory physicians spend more than 5 hours on the electronic health records." (...)

In other words, the AMA isn’t offering a software product. It just runs this process, keeping a list of codes that map to different medical procedures. You would think it would be free, a standard for everyone to use. But it’s not, and the AMA is able to charge a royalty for the license to use those codes. Every medical software company seems to have CPT codes and royalties built into their workflow.

Other similar systems are public. For instance, there’s the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, which are used by most other countries for free. ICD and CPT codes are complements, not substitutes. ICD is a list of diagnoses- “this patient has depression” “this patient has a pulmonary embolus” while CPT is a list of procedures “I talked to this patient for 60 min” “I did this surgery on this patient.” Most billing systems require both codes, basically the insurer is saying “what did you do” (CPT) and “why” (ICD)? But only one is copyrighted. To put it differently, this situation is a bit like if Fedex owned and designed the zip code system, and got to charge anyone who used a zip code.

The total amount of money to the AMA is relatively small, at least compared to overall cost in our health care system. It’s roughly $300 million a year to the AMA in royalty payments. That’s not nothing; but the impact is far more significant on the politics of health care. To understand why, it helps to start with the importance of this particular trade association.

The AMA is the “doctor’s lobby,” and it has been a powerful force in American politics since it was founded in 1847. The rich American doctor was a 20th century community leader, or a petty tyrant, whichever you might believe. Americans respected their physicians, and doctors were conservative and locally rooted, able to speak with authority on matters of public health. They generally feared the state, but also feared corporate control.

The AMA, as such, jealously guarded this position, routinely opposing government attempts to provide universal health care through a centralized administrative public apparatus, haranguing Democrats as seeking to foster “socialized medicine.” And it worked. The AMA beat Franklin Delano Roosevelt, it beat Harry Truman, and it beat Bill Clinton. The threat of corporatization was perceived by medical professionals as coming from the left.

But in the last 20 years, this dynamic has changed, because most doctors now work for large corporations. The old days of hanging up a shingle in a solo or even small group practice is gone because it’s no longer possible for an individual to bargain with the giants that manage the reimbursements, hospital systems, and payment arrangements necessary to be a doctor. Curiously, the AMA, which one would think has some interest in opposing the mass corporatization of its membership, doesn’t seem to care. For instance, the AMA only took a stance on private equity two years ago, long after its membership had transitioned from majority independent practitioners to majority corporate employees. And a key reason might be because it doesn’t make its money by serving doctors anymore. It makes it from the CPT code monopoly it uses to extract from doctors.

Let’s look at some numbers.

If you look at AMA financial disclosures from 2004 to 2023, you’ll notice three big trends. First of all, dues membership is down. In 2004, it was at $48 million. By 2023, it fell to $33 million. Second of all, revenue is way up, from $243 million to $468 million. And third, there’s an item - “royalties” - that explains it. Royalties, which come largely from CPT code revenue, were about a fifth of the AMA revenue in 2004, at $45 million. In 2023 they were at $308 million, 62% of all revenue, including all the profit, most of the overhead, and the lucrative executive salaries, which have increased by 10x since 2004.

The original CPT codes came out in 1966 to coincide with Medicare, but were published as a book updated annually. It was when electronic medical records took off that the revenue stream picked up. (...)

This situation isn’t just a case of unfair rent extraction, though it is certainly that. It’s also a case of political capture of the AMA. At any point, the Secretary of HHS could choose to revisit its standardization on top of CPT codes, and either foster an alternative, allow competition, or demand that the AMA cut prices. There are alternatives. There are ICD codes. There’s also something called SNOMED, which stands for the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms, which is paid for by at a national level. It’s much cheaper than the CPT codes; Japan, for instance, pays less than $1 million. Switching over to a new system, or even allowing a new system would take a lot of effort. A much simpler change would be Congress passing a law invalidating copyrights for public medial standards, such as CPT codes. It’s ridiculous that a public standard on which everyone must operate is subject to extractive royalty payments. The government has a lot of power here, and could actually start to exert it.

Friday, April 4, 2025

Manufactured Chaos

Musk and seven DOGE staffers—all of them men—appeared on Fox News Thursday, where the world's richest person called the Trump administration's crusade to eviscerate the federal government under pretext of improving efficiency "the biggest revolution in the government since the original revolution" in 1776.

Acknowledging that DOGE's wrecking-ball approach to government reform is getting "a lot of complaints along the way," Musk said: "You know who complains the loudest, and with the most amount of fake righteous indignation? The fraudsters." (...)

Responding to what she called Musk's "absurd claim," Nancy Altman, president of the advocacy group Social Security Works (SSW), said Friday that "the truth is that Social Security has a fraud rate of 0.00625%, far lower than private sector retirement programs."

"It is Musk and DOGE who are inviting in fraudsters," she continued. "Scammers are already rushing in to take advantage of the confusion created by DOGE's service cuts."

Critics have denounced the Trump administration for sowing chaos at SSA and other federal agencies by planning to lay off thousands of workers, slash spending, and implement other disruptive policies. Cuts in SSA phone services were reportedly carried out in response to a direct request from the White House, which claimed it is simply working to eliminate "waste, fraud, and abuse."

"The truth is that Social Security has a fraud rate of 0.00625%, far lower than private sector retirement programs."

This "DOGE-manufactured chaos," as Altman calls it, has already led to the SSA website crashing several times in recent weeks and hold times of as long as 4-5 hours for those calling the agency.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass) on Thursday noted that while it would be clearly illegal for President Donald Trump and DOGE to cut Social Security benefits without congressional authorization, there are other ways for the administration to hamstring the agency.

Referencing a new in-person verification rule that was delayed and partly rolled back this week, Warren said:

Democratic lawmakers and others argue that the Trump administration's approach is "a prelude to privatizing Social Security and handing it over to private equity," as Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) said earlier this week.

"Improving Social Security doesn't start with shuttering the offices that handle modernization, anti-fraud activities, and civil rights violations," the senator asserted. "It doesn't start with indiscriminately firing or buying out thousands of workers, and it doesn't start with restricting customer service over the phone and drawing up plans to close field and regional offices."

[ed. Making government deliberately dysfunctional. Actually, it would be scarier if they really believed they were making it better.]

The DOGE staffers repeated unfounded claims that Social Security is riddled with fraud; that in some cases, 40% of calls to the Social Security Administration phone center are fraudulent; and that millions of people aged 120 and older are registered with SSA.

Acknowledging that DOGE's wrecking-ball approach to government reform is getting "a lot of complaints along the way," Musk said: "You know who complains the loudest, and with the most amount of fake righteous indignation? The fraudsters." (...)

Responding to what she called Musk's "absurd claim," Nancy Altman, president of the advocacy group Social Security Works (SSW), said Friday that "the truth is that Social Security has a fraud rate of 0.00625%, far lower than private sector retirement programs."

"It is Musk and DOGE who are inviting in fraudsters," she continued. "Scammers are already rushing in to take advantage of the confusion created by DOGE's service cuts."

Critics have denounced the Trump administration for sowing chaos at SSA and other federal agencies by planning to lay off thousands of workers, slash spending, and implement other disruptive policies. Cuts in SSA phone services were reportedly carried out in response to a direct request from the White House, which claimed it is simply working to eliminate "waste, fraud, and abuse."

"The truth is that Social Security has a fraud rate of 0.00625%, far lower than private sector retirement programs."

This "DOGE-manufactured chaos," as Altman calls it, has already led to the SSA website crashing several times in recent weeks and hold times of as long as 4-5 hours for those calling the agency.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass) on Thursday noted that while it would be clearly illegal for President Donald Trump and DOGE to cut Social Security benefits without congressional authorization, there are other ways for the administration to hamstring the agency.

Referencing a new in-person verification rule that was delayed and partly rolled back this week, Warren said:

Say a 66-year-old man qualifies for Social Security. Say he calls the helpline to apply, but he's told about a new DOGE rule, so he has to go online or in person. He can't drive. He has trouble with the website, so he waits until his niece can get a day off to take him to the local office, but DOGE closed that office, so they have to drive two hours to get to the next closest office. When they get there, there are only two people staffing a 50-person line, so he doesn't even make it to the front of the line before the office closes and he has to come back. Let's assume it takes him three months to straighten this out, and he misses a total of $5,000 in benefits checks, which, by law, he will never get back."This scenario is a backdoor way Musk and Trump could cut Social Security," the senator added. "That's what I'm fighting to prevent."

Democratic lawmakers and others argue that the Trump administration's approach is "a prelude to privatizing Social Security and handing it over to private equity," as Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) said earlier this week.

"Improving Social Security doesn't start with shuttering the offices that handle modernization, anti-fraud activities, and civil rights violations," the senator asserted. "It doesn't start with indiscriminately firing or buying out thousands of workers, and it doesn't start with restricting customer service over the phone and drawing up plans to close field and regional offices."

by Brett Wilkins, Common Dreams | Read more:

Image: Fox "News"

Steve Rattner on Just How Bad Things Will Get Under Trump’s Tariffs

In this episode of “The Opinions,” the deputy Opinion editor Patrick Healy and contributing Opinion writer, investor and economic analyst Steven Rattner break down how President Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs” are already shaking the global economy — and it hasn’t even been 24 hours. (...)

The transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Patrick Healy: I’m Patrick Healy, deputy editor of New York Times Opinion. And this is The First 100 Days, a weekly series examining President Trump’s use of power and his drive to change America.